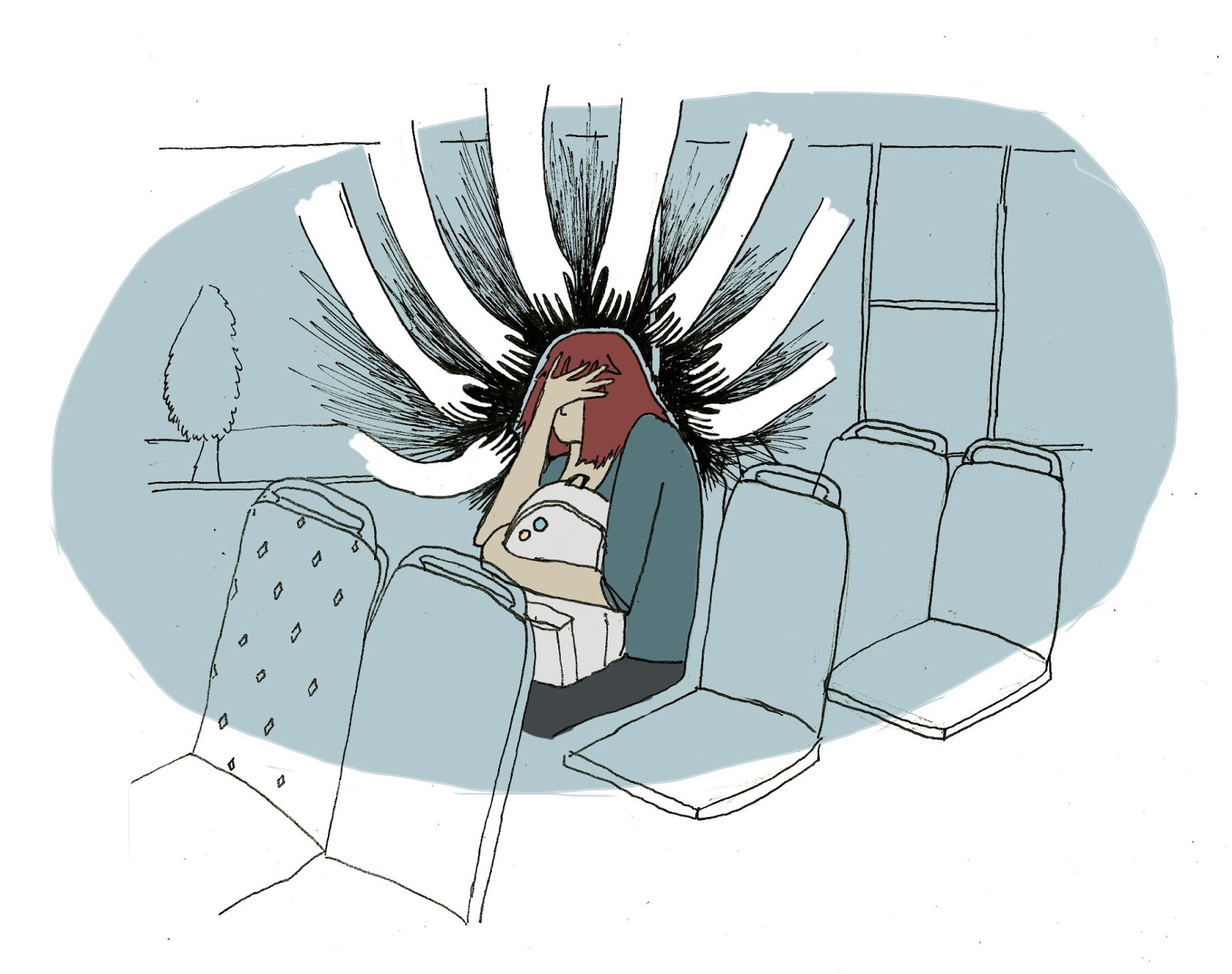

pain

Monsters In My Head Or How I Battled And Defeated Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder – Part 1

Illustration by Jess Marshall

When I was six, I started imagining that something or someone will come out from behind my drawer and hurt me. I had moved with my family into a new apartment, and each time I entered my room, I was looking obsessively in that corner, fearing that something bad was about to happen to me.

When my folks were home, I felt safe. When I was left alone for a couple of minutes, fear and worries overwhelmed me, and lasted until one of my parents returned.

Sometimes I was so terrified of what might come out from behind the drawer, that I followed my parents around the house, without telling them why. I thought it was normal. By the time I turned 32, the something, the abysmal evil from behind the drawer took many forms: prison, cancer, madness, heart attacks, mental illness and death.

Last summer, I decided it was finally time to fight my imaginary demons. I went to two psychiatrists, three psychologists and yet another two who counseled me over the phone. I read as much as I could about the monsters hiding beneath obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and put everything I learned in this text:

“Three big fish, with luscious, turquoise tails, swirl around tangled weeds. I’m sitting in an armchair, rubbing my sweaty palms against the white blanket while gazing at the aquarium. In front of me, in a different armchair, sits Sorin, my therapist, arms folded against his chest. A minute, perhaps two go by; profound silence in the room.

The psychiatrist clears his throat: “I’ll tell you a joke; you look like the kind of guy who likes jokes. It’s one of those psychiatrist jokes, psychologists, whatever:”

“A guy goes to the doctor and says: “Doc, I haven’t slept all night!”“How come?”, asks the doctor. “Well I sat down on the bed and after 10 minutes I started thinking, what if there’s someone under the bed? I get up, look under the bed, no one’s there. I sit back down, start falling asleep but then the same thought strikes again, “what if I haven’t looked properly, what if there actually is someone under the bed?” I get up, look under the bed, still nothing. I go back to sleep, after a couple of minutes I’m thinking, “what if someone appeared under the bed in the meantime?” I get up and look again, nobody’s there. And this went on for the rest of the night.”

The doctor looks at him and says, “Yes, it’s OCD, you have to do psychoanalysis for five years,come inthrice a week, 100 dollars per session”. The guy ponders for a while, “sweet fuck, three times a week for five years, 100 dollars each session”, thanks the doctor and leaves the office.

After a week, the doctor sees the patient walking on the street, approaches him and says, “Weren’t you the one with the OCD? How’s it going, did you start therapy?”, and the guy says, “Nah, I took care of it real quick, cost me 10 dollars and I’m perfectly fine.” “Well how did you do it?” asks the doctor, and the guy replies “It’s simple;I cut off the bed legs.”

“Okay, this was the joke part”, says Sorin. In reality, things are a bit different when it comes to this disorder. Sure, you can cut off the bed legs, but you’ve also got a drawer and a wardrobe and book shelves where anyone and anythingcan be hiding. What are you going to do about that?

“Been there, done that”, Sorin told me some other time, “I moved from the 7th floor to the 2nd.” We both laughed about it back then, the way you’d laugh at someone who moves a couple of floors below, to decrease his probability of jumping out the window. These are the workings of an anxiety-riddled mind, it constantly reminds you, in hushed tones, that there is a chance, a possibility for you to jump out the window. Moving down a couple of floors is the equivalent of cutting off the bed legs.

There are, of course, some more such thoughts specific to suicidal obsessive disorders – you might, for instance, jump in front of speeding cars, throw yourself on the subway tracks, drink bleach, engage in precarious activities involving knives, hang yourself and many other such violent instincts which arise out of the blue, when you least expect them.

As regards suicidal obsessive disorder, the fear is usually accompanied by more complex thought patterns: “What if I’m depressed and I’ll end up killing myself?”, “there are signals that I have to kill myself”, “what if I actually do want to kill myself?”; “is it possible I might kill myself?”; or simply other intrusive, spontaneously occurring thoughts along the lines of “I want to kill myself”, thoughts which are completely unrelated to anything you’re doing at the moment.

It’s not me who came up with all these obsessions, they’re classics, impersonal.

At some point, they actually get boring and finally, end up being completely and utterly uninteresting.

In fact, that’s what suicide looks like in the context of obsessive-compulsive neuroses. According to academic literature, “those who genuinely want to kill themselves don’t make an obsession out of it”. “Obsessions don’t come true”, according to my psychiatrist Sorin, who’s a really experienced guy and an author in the field. At some point, after me incessantly asking him during each session “Am I depressed? Am I depressed? Can’t it be depression?”, Sorin got up from his armchair and said, “You don’t have depression, let me put your mind at ease about it” and offered me a book he wrote about depression; at the end of the session, I asked him if it’s possible I’m going crazy, to which he replied, “no. When I write a book about schizophrenia, I’ll give that one to you as a gift as well.”

Original Romanian version: casajurnalistului.ro/boala-indoielii

—

Mihnea Mihalache-Fiastru is licensed in Psychology, essay and fiction writer, author and contributor since 2001 for Hustler, Vice and many other publications and websites

Be the first to write a comment.

Your feedback