empathy

The Male Gaze: Why We Live In A World Of Highly Sexualized Female Icons

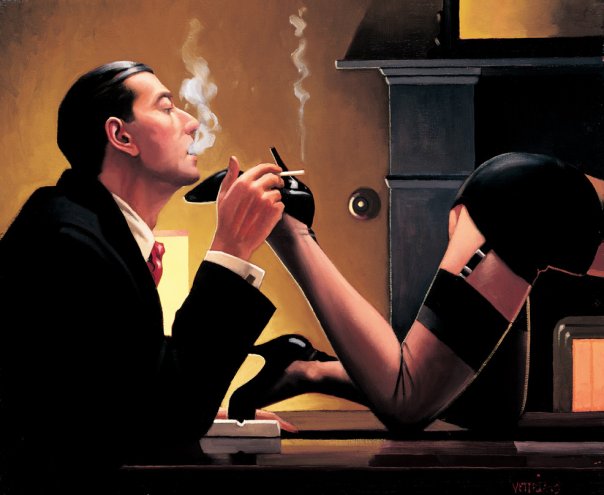

Painting by Jack Vettriano

The camera pans across an early morning beach, until it happens upon a lone woman walking in the distance. Focusing upon the back of her ankle, the lens then glides up and over the curves of her body. In the distance, another figure comes into sight. Zooming in, we note it’s James Bond, our very reason for being in the cinema. Like the woman, he cuts an attractive figure, but unlike her, we’re far more concerned with the activity that occupies him, than his beauty.

This is the male gaze: a concept outlined by Laura Mulvey in 1975. That camera is wielded by a man capturing the story of a male protagonist. As the story unfolds, men in the audience relate to Bond, seeing things from his perspective. While they look upon the women swooning around him, as mere objects of desire.

And the women seated in the cinema, they too are forced to take in the scene from this male perspective.

Mulvey may have coined the phrase, but the male gaze has been guiding the tools that have produced the visual arts throughout the ages. Today, the gaze pervades popular culture, leading to the highly sexualized female avatars in video games and the production of the airbrushed images peering out of women’s magazines.

It’s the chief commodity in advertising. If a man buys the product promoted by an alluring woman, he may just gain her hand in marriage. While if a woman makes the purchase, she’ll garner that very gaze.

Take the example of my friend, Sylvia. Even on days when she stays at home, she makes sure she’s dressed to the hilt with full makeup. When asked why, she replies that it makes her feel better and there’s always the chance that out of the blue someone may call.

This internalisation of the male gaze relates to French philosopher Michel Foucault’s theory of the gaze. In his reckoning, since the eighteenth century, Western society has developed a system of control.

A key motif of this system is an architectural structure called the Panopticon: a circular building with a central observation tower. Inside this tower is a watchman and although he cannot give his constant attention to every occupant, there’s always the chance he’s looking at you.

This structure has influenced the way subsequent institutions – such as factories and prisons – have been built. And as technology progressed, that watchman has been replaced with the all-pervasive surveillance camera. The uncertainty as to when they’re being watched has led citizens to internalise society’s norms.

And so to the patriarchal norms projected by the male gaze shape the way women and men act and how they are perceived: just like Sylvia being constantly on show for her non-existent visitor.

But there are cracks in these polar gender stereotypes.

Every night, in cities around the world – from Bangkok to Sydney to Berlin – you can take in a drag show. Dressed in women’s attire, male performers dance and cavort on stage. The crowd look upon them in much the same way that they do female performers. And yet, after the show when the makeup and stockings come off, the spectators react to those same performers as males once more.

As queer theorist Judith Butler understands it, the performance of the drag queen reveals there’s nothing inherent in gender roles. Butler perceives the ‘normal’ ways women and men predominately act in society as performance. The constant repetition of these roles in daily life and the media gives them authenticity. But as can be seen in the affectation of a style of female persona in drag performance, these roles aren’t so solid.

Over the last year, transgender people have come to the fore of popular culture. But at the same time in the United States, violence towards trans women has risen, with an almost doubling in the number of homicides. In a recent interview, Butler pointed out that trans women, in giving up their masculinity, reveal that it’s not an intrinsic part of themselves.

In the case of the murders, the men compelled to carry them out, may have done so feeling that what they thought was their innate position of power was being threatened.

Indeed the male gaze and its established heterosexual norms may be starting to unravel. Last year, gender fluidity entered pop culture, as a string of public figures from Miley Cyrus to Lily-Rose Depp announced they were ‘not straight.’ However, mainstream media attention, doesn’t guarantee real change.

The recently passed David Bowie was a central figure in the gender fluidity movement of the early 70s. Along with him, transgender icons like Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling from the Warhol Factory took to the screen. But while the public were transfixed by these transgressive figures, in the long run the attention remained mere fascination.

—

Paul Gregoire is a Sydney-based freelance journalist and writer, with a passion for travel and a focus on drug law reform, Indigenous issues, gender and asylum seekers.

Be the first to write a comment.

Your feedback